This essay appears in Issue 4 of the Mars Review of Books. Visit the MRB store here.

Alexandre Kojève: A Man of Influence

edited by Luis J. Pedrazuela

Lexington Books, 260pp., $80.54

If the nineteenth century was a Hegelian century, fundamentally shaped by the suppositions and limits of Hegel’s philosophy, and the twentieth century was a Nietzschean century, the twenty-first century is the century of Alexandre Kojève.

Everywhere one turns one finds him waiting. Already in 1989 it was Kojève who inspired Francis Fukuyama’s famous proclamation of the “end of history” and today it is Kojève who grounds the project of diversity, equality and inclusion which defines post-historical politics. No wonder Judith Butler wrote her dissertation on Kojève. What is today attacked on social media (itself the supreme globalizing, homogenizing power) as “globohomo” is what Kojève called “the universal homogenous state,” the final state of man in which political and ideological struggle is over, and individuality is suppressed by a total administrative state.

Far more than Foucault or Herbert Marcuse, Kojève is the master thinker of the current year regime. But his significance isn’t the effect of a spell he cast, but his rigorous formulation of the direction of travel. In a half-deranged epoch desperately in search of solutions, Kojève proposed a description which returned the world to coherence, albeit a disturbing coherence. His contemporary equivalent in this respect is Nick Land.

In his 1930s seminars at the École des hautes études on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, delivered to an audience comprising almost every important Paris-based intellectual of the era (including Raymond Aron, André Breton, Georges Bataille, Frantz Fanon, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and perhaps above all Jacques Lacan, who designated Kojève as his master and based his influential theory of ‘the mirror phase’ on his teachings) Kojève developed a merciless vision of historical progress, the drastic conclusion of which was only partially grasped at the time.

History, Kojève argued, started with the fear of death and culminated with the “abandonment of individuality, that is in fact of humanity” in a final state comprised of “living bodies with human form, but emptied of spirit.”

At the beginning of historical time, according to Kojéve, one party risks death to impose his will, and the other surrenders to preserve his life: This settlement sets in motion the grand narrative of the master-slave dialectic as the engine of historical progress. With his labor, the slave transforms the world and himself; with his dependence on labor the master atrophies. Mankind advances and the world becomes humanized: The terror of natural authority softens, and traditional hierarchies lose their force. Finally the slave becomes conscious of his absolute power of genesis. The world becomes an artificial “second nature” and even the concept of mastery vanishes into the historical past.

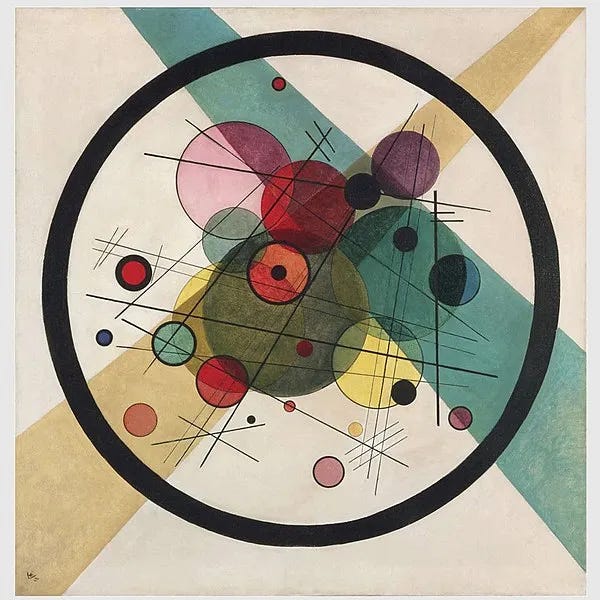

Contemporary rhetoric which designates inegalitarian nature as tyranny (“fascism”) rearticulates Kojève’s conclusions in a semi-literate ideological register. Nature for Kojève occupies the dialectical pole of the master; only what is constructed through labor is freedom. Posthistorical humans, becoming almost mindless, finally “construct their edifices and works of art as birds build their nests and spiders spin their webs . . . perform musical concerts in the manner of frogs and cicadas . . . play like young animals, and . . . indulge in love like adult beasts.” The “concrete” paintings of Kojève’s uncle Wassily Kandinsky offer a visual preview. Presenting what Kojève called a “uni-totality that exists in the same way as do trees, animals, rocks, men, States, clouds,” this amorphous nirvana now expresses itself post-artistically through the misshapen and genderless humanoids of the “flat design” illustration system that defines the “globohomo” aesthetic from Facebook to Hinge.

This is Kojève’s end of history: not Fukuyama’s utopia of Lockean liberalism, American individualism and free markets, but a boring dystopia of nihilistic consumerism, brainwashing, spiritual exhaustion, and death.

***

Kojève always denied he was offering an original philosophical vision (which he further denied was even still possible) but was merely explicating, or at most updating, Hegel. The main contribution of this highly academic collection of essays is to demonstrate this isn’t true.

In his elegant introduction, the editor of Alexandre Kojève: A Man of Influence, Luis J. Pedrazuela, compares Kojève to a Matryoshka Doll “whose wholeness is not comprehensible if a figurine is left out.” The most prominent doll in the set is undoubtedly Hegel, but Kojève’s presentation of the fundamentally conservative thinker is highly selective and even perverse; in a 1948 letter to Vietnamese philosopher Tran Duc Thao he himself admitted that his reading of Hegel was a work of propaganda. In the Phenomenology of Spirit the master-slave dialectic is almost an aside: It takes up a few brief pages, and is considerably less important in Hegel’s account of self-consciousness than the unhappy consciousness which creates a link between individualistic striving after recognition and communal conditions including tradition, ethics, and family life.

As political science professor Waller R. Newell points out in his chapter, modern man for Hegel is not just the synthesis of a master and slave but amalgamates a “wealth of shapes” including Master, Slave, Stoic and Skeptic. But here as elsewhere, Kojève rejects mediation in order to stress contradictions, and deliver them up to the Ragnarök of his ultimate liquidation.

When not representing himself as Hegel’s ventriloquist, Kojève identified as a Marxist, and sometimes referred to himself as a “strictly observant Stalinist.” Fundamentally, he shared Marx’s radically eliminative instincts, his Left Hegelian premises, and above all, his commitment to atheism. Like Marx, Kojève aimed to eradicate theology from human thought. “Only one serious dilemma remains for us,” he proposed in his Hegel seminar, “the dilemma: Theology or Philosophy.” Yet, just as Marx’s own thought is shot through with crypto-messianic mythologems, Kojève’s vision is much less secular then it appears at first sight.

As Kojève’s biographer Jeff Love emphasizes in his own contribution to this book, Kojève drew a hugely significant subterranean influence from Buddhism: Among the stranger texts to be found in Kojève’s vast, mostly unpublished corpus of apocrypha is an almost incomprehensible imaginary dialogue between Descartes and the Buddha on the nature of thought, existence, and inexistence, written in Warsaw in June 1920, when Kojève was eighteen. A year later, Kojève began to study Buddhism in earnest in Heidelberg under the tutelage of German Indologist Max Walleser. After learning Sanskrit, Tibetan, and Chinese he started to translate the second century Mahāyāna thinker Nāgārjuna, from whom he picked up the concept of Śūnyatā, or emptiness, boundlessness, nothingness.

It was from this perspective that Kojève was able to welcome the historical vision of human extinction which philosopher José María Carabante, in his own chapter, calls “a philosophy of death”—in which suicide is upheld as the supreme form of freedom. This fatalistic conjecture struck a chord with the brooding interwar group of intellectuals in Paris, at the same moment that historian Oswald Spengler was prophesizing the inevitable, cyclic decline of the West. But while Spengler’s vision concluded in a melancholy romanticism, Kojéve’s slyer, more cynical temperament proved more decisive politically.

The title of this volume is well chosen: Kojéve was more a vector of influences than a personal source of them: In the end, his power rested on his success in narrating the state of the world as it transformed from liberal modernity to managerial democracy. His post-war career as a civil servant in the French Ministry of Economy and Finance was in its own way as epochal as Hegel’s infamous glimpse of the world-spirit on horseback: Kojéve in his office as the spirit of a world without spirit, working efficiently for human extinction.

Raymond Aron wrote in his Mémoires that the theme of Kojève’s seminars was both the arc of world history and Hegel’s Phenomenology, with each illuminating the other. The complex intellectual portrait of Kojève which emerges through this volume likewise succeeds in illuminating the contemporary world. Kojève, a stunted distortion of Hegel, mirrors a world which is likewise a stunted distortion of the long nineteenth century, in which history has transformed from a myth into a spectacle, racket, and farce.

The final question this book poses, albeit implicitly, is how our epoch of Kojève will conclude. Kojève’s dialectical logic is as merciless as Greek tragedy, but humanity no longer has a feeling for tragedy, and Kojéve’s attempt to close the historical circle of consciousness is ultimately more absurd than cathartic. Individual consciousness, alas, cannot be dissolved into pure collectivity. We are, unfortunately, individuals, with all our pointless problems and deranged desires. The fact that Kojève is compelled to conceive (and now we are compelled to destroy) an inhuman machinery devoted to suppressing individuality already testifies to individuality’s irrepressible nature. The end of history is not even a dystopia, but a dead end, defined by an insurmountable obstacle that cannot be overcome, like the last speck of self-consciousness that no quantity of sedatives eliminates. The dark comedy of both Kojève’s position, and ours—a comedy that the mordant Kojève himself would have no doubt enjoyed—is the comedy of someone who wakes up after a failed attempt at suicide, and learns that he has overdosed on hallucinogens instead. We can only pray that the Kojévian century will be short.