The Island of Eternal Life

One reporter's journey to the private, tech-forward Central American territory at the center of the movement to cure death

It was a clear tropical morning on the Honduran island of Roatan, and with the naked eye you could see right across the channel to the mainland, past the cruise ships and diving boats that dominate the coastline, looking out from a small city known as Coxen Hole—named for a British pirate who settled there in the 17th century to pillage the Spanish armada. The landscape may have looked like any other tropical beach hub—turquoise water and fine-grain sand surrounded by overgrown jungle and shanty towns. It's also the site of a civilizational experiment to build a state within a state called Próspera—a special economic zone with its own trade laws and security force—that’s flooding the island with international investment, and American business-types wearing linen button-downs and ankle-high chinos. Amid the swerving motorbikes and burning garbage heaps, there’s an international airport offering direct flights from Miami, Dallas, Houston, and Atlanta, herding in tech workers with laptop jobs and wary investors seeking what they call an “exit” from American society. They have come to Honduras, and Roatan in particular, where Próspera is located, in search of what they call a new “frontier,” Galt’s Gulch in the Caribbean.

To be admitted into Próspera, you first have to be approved for entry by one of the organizations with a presence in the territory. I wouldn’t have gotten approved if not for Mark Hamalainen, a longevity educator and entrepreneur, who vouched for me with the organizers. A few days earlier, I spoke to him over Zoom. Showing up in a black muscle tee that said, “Don’t Die,” he asked me if I wanted to live forever, and I replied tentatively, “yes,” as if it were a secret passcode. The next day I was eating tacos in the Miami airport watching a Mexican chad in a crypto hoodie trade NFTs while sucking down an oversized Slurpee. I hopped on the connecting flight wondering if I was heading to the real life island of Doctor Moreau, fantasizing about pig men and human centipedes. Just how deep did this longevity thing go, I wondered. What could go wrong in a libertarian playground on an island with no rules?

The event I’d come to observe was called Vitalia, also known as the “city of life,” a “longevity network state pop-up city” sponsored by VitaDAO, a “decentralized science” company that had recently raised $4.1 million from Pfizer. Scientific researchers and tech workers from around the world were descending on Roatan to start a “county in the cloud,” comparing nation building to the process of building a startup. Some countries have populations less than a million people and GDPs the size of a startup, the logic goes. Could a startup nation, founded by a tech mogul with millions of followers, eventually match those numbers? Vitalia intended to prove that it could. LARP or not, the money was real, and so were the people and the guns and the lawyers. Descending into Roatan, I started to hum that Warren Zevon song about ditching a Russian spy in Havana and hiding in the Honduran hills. “I'm a desperate man/ Send lawyers, guns and money/ The shit has hit the fan.”

The idea for this experiment had spawned in 2013 at a tech conference in Cupertino, California. On the same stage where Steve Jobs had handed down the Macintosh Computer like the tablets of Moses, a short-haired Indian man with round spectacles and an oversized sweater stood on the stage at Y Combinator's Startup School and delivered a lecture entitled “Silicon Valley’s Ultimate Exit.” His name was Balaji Srinivasan, an ex-Stanford professor turned entrepreneur, then at the helm of a genomics company and co-teaching a startup MOOC billed as the “spiritual sequel” to Peter Thiel’s computer science course at Stanford University. “Is the USA the Microsoft of Nations?” the opening slide read. “Let’s consider the evidence.”

If America were a software business, the presentation starts, its “codebase” (the Constitution) would be 230 years old and written in an “obfuscated language.” America treats its key “suppliers” ruthlessly (he points to an image of Muammar Ghaddafi and Saddam Hussein); it’s focused primarily on rich enterprise customers (with the logos of the oil company Halliburton, and Booz Allen Hamilton, the consulting firm); and there’s systematic FUD over security issues, a crypto term meaning “fear, uncertainty, and doubt” (with an image of Edward Snowden and the NSA). For the two weeks before this event, the U.S. government had been shut down over a longstanding debate over Obamacare. This was Srinivasan’s sixth bit of evidence: things aren’t even working. And yet the world is still forced to buy its products, he said, pointing to an image of an aircraft carrier floating in the ocean.

When a system is no longer working, he went on, you can choose to reform it from within— exercise your voice—or you can leave the system altogether and start something new. Srinivasan transposes the concept into startup terms. Startups exit commercial systems when they innovate, he argues, just as citizens exit nations when they immigrate somewhere new. “Exit amplifies voice,” he said, because voice gets more attention when people are leaving in droves. “Exit is the reason why half this audience is alive,” because our ancestors left countries run by tyrannical regimes. And exit is something we need to preserve. It’s about giving people tools to oppose bad policies “without getting involved in politics.”

This is increasingly important, Srinivasan said, because we’re about to witness a great backlash to the power of tech in America. Since the late nineties, Silicon Valley startups have disrupted all the previous centers of America’s power—from New York and its influence on the news, Boston and its control of higher education, LA and its production of entertainment, and even DC, and its hold on governance. “It’s not necessarily clear that the government can ban something that it wants to ban anymore,” he said, pointing to the examples of Uber, Airbnb, Stripe, and Bitcoin. Silicon Valley is becoming more powerful than all of the other power centers combined, he said, and soon the old power centers are going to start blaming the failure of the economy on us, claiming “that it was the iPhone and Google that done did it, not the bailouts, the bankruptcies, and the bombings.”

“The ultimate counter-argument is actually exit,” he said. Just as Bitcoin created an escape valve to “exit” the traditional financial system, other projects will create opportunities to sidestep political rules. Larry Page wants to set aside parts of the world for technological experimentation. Marc Andreesen wants to see an explosion of countries. Peter Thiel is funding the creation of seasteading habitats in the middle of the ocean. Elon Musk wants to build a colony for humans on Mars. All these little exits, Srinivasan said, are part of a grand strategy: to build a new world on the foundation of software, with Silicon Valley at the forefront.

In the years that followed, Srinivasan’s star continued to rise and rise. Until in 2017, at the behest of his friend Peter Thiel, he was riding up the elevator at Trump Tower to meet the newly elected President about a role as the head of the FDA. He didn’t get the job, but in the intervening years he sold his genomics company for $375 million, followed by his Bitcoin mining company, which he sold to Coinbase for $120 million, finding himself “acqui-hired” as CTO. The job was short lived, and so was his stint as general partner at venture capital firm a16z. But it didn’t matter. Because as the culture swilled around him, fulfilling his prophecies, he stepped into what might be considered his penultimate role: Twitter troll extraordinaire. Two crypto bull cycles and a global pandemic later, and soon he racked up six-hundred thousand followers and a reputation as a soothsayer. Trust in global institutions plummeted, just as he and his friends became “post money,” as the podcaster Tim Ferris once put it. So that when he self-published “The Network State,” in 2021, on the Fourth of July, his audience was primed to hear its message. If the 2013 lecture was a warning call, “The Network State,” in 2021, was a playbook.

“The Network State” argues that, given the current technological conditions, a group of people on the internet with enough money, power, and social coordination can organize around a single moral “commandment” (like “end death,” for a longevity network state) and eventually gain recognition as a country from the United Nations. If Liechtenstein or Vatican City can be considered countries, Srinivasan argues—city-scale administrative regions, with sub-million populations and GDPs no larger than a startup—then why not a group of tech people organized on the internet, led by a tech mogul with political clout and millions of dollars and followers?

The idea is that, at a time when people spend most of their lives online, the connection between people who share niche political interests, like a passion for Bitcoin or longevity, surpasses what they might feel for their neighbors in meatspace. And as the internet has made it easier for people to find each other, organize, and pool their resources, it's creating the possibility for them to start building their own societies; ones that are “cloud first, land last, but not land never.”

As a matter of process, Srinavasan imagines network states starting out as an accumulation of private properties, like a national Soho House, organized with a cryptocurrency and a DAO infrastructure; basically a “group chat with a bank account.” “Subscriber-citizens” would enter these properties with cryptographic e-passports, and slowly accumulate influence and resources until they begin to negotiate on an international scale. The success of the best projects would be used as case studies to prove their legitimacy, providing a template to be replicated over and over. It would cause a “Cambrian explosion” of network state projects. Whereas America is collapsing under the weight of its own internal discord, Srinivasan argues, experiencing what he calls “civilizational diabetes,” the network state system is just beginning. Culture wars, bloated public funding, carnivalesque elections, failing public services—these are all side effects of nation-states failing “legacy” infrastructure. The rise of network states are kicking off a fin de siècle of “software eating the world,” only now it’s applied to governance.

Come 2023, the shovels hit the pavement. In New York, a company called Praxis raised money from a who’s who of venture capitalists, including Peter Thiel, and began to court the city’s ferment of anti-establishment eccentrics. It announced plans to set up a city somewhere in the Mediterranean. In Silicon Valley, a Nigerian emigree started a “digital nation” called Afropolitan, a DAO attempting to bring the African diaspora online. In December 2023, Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin sponsored an event called “Zuzalu” in Montenegro, for a two-month “proto-network state with longevity at its heart.” And in January 2024, in Próspera, there’s Vitalia, on the island of Roatan in Honduras.

Driving past the guards at Próspera’s “border check”—a tolling station with some armed men in uniform, smoking cigarettes—I wondered if this was the “Cambrian explosion” of network-worshiping subscriber-citizens Srinavasan had predicted. Or were the guards merely cogs in an elaborate tax evasion scheme, guarding a gated community LARPing as a country? Were they angry about the decaying nation-state and its “legacy” infrastructure of American bankers and politicians? Or were they just doing a job for some tech people orchestrating a real estate bubble for regulatory arbitrage? Was this colonialism?

The future, Srinavasan wrote in 2015, is nationalists vs technologists: “A full-throated, jealous defender of borders, language, and culture (nationalists). Or a rootless cosmopolitan with a laptop, bent on callow disruption (technologists).” Did the guards know which side they were fighting for, manning these gates? Did I?

The genesis of the city-state experiment that is Próspera goes back to 2009, when it was still possible for a Stanford economist to stand atop a gilded stage at TED Oxford, wearing a blue button down and slick gray blazer, and recite their big “inspiresting” idea that could positively change the world. In July of 2009, one such academic, a Nobel Prize-winning economist named Paul Romer, did exactly that—offered his big idea worth sharing: a political innovation he called charter cities.

The idea was simple: the key difference between places that grew rapidly and those that languished in the global economy, remaining trapped in a cycle of low growth, was the quality of their rules. Good countries, like those in the West, had strong rules and strong institutions, which produced trust on the part of investors, and boosted the economy. While those in the less developed world were addled with corruption, crime, and instability, which made it difficult for their economies to develop. Places like Hong Kong and Singapore, which had both embraced the spirit of capitalism while remaining within a wider system of socialist rule, were precursors to the charter city model. The people in Hong Kong or Singapore were no different from those on mainland China: the difference was institutional. So to help the rest of the world develop, Romer proposed that the Hong Kong model be exported elsewhere. To make it work, all you’d need was a sponsor country, who could import their resources and governance style, and a new legal charter, mapped at the outset, to provide a transparent view of the system-to-be.

A few months later, a group of politicians from Honduras reached out to Romer to ask for help. Fresh off the success of a military coup, the National Party of “Pepe” Porfirio Lobo, and his team of American-educated advisors, were looking for a way to boost the country's economy and expand its web of “export processing zones (EPZs),” which had been established there in the 1970s and grown from a nine-thousand person labor force to a hundred-thousand by the early nineties. Their solution was the Region Especial de Desarrollo (special development region), or RED. REDs would grant special authority and land to a foreign partner-nation who could determine their own immigration policies, hire their own police force, set up schools, and enter into trade agreements with other countries. With help from Romer, the concept was ratified in the Honduran congress in 2011 through a constitutional amendment. “Who wants to buy Honduras?” asked the New York Times. In The Atlantic: “Should Struggling Countries Let Investors Run Their Cities?”

The first investment in Honduras came from an American group called Future Cities Development, started by Patri Friedman, the grandson of Milton Friedman, and founder of the Seasteading Institute. It also took investment from Peter Thiel, among others. As Quinn Slobodian argues in his 2023 book, Crack-up Capitalism, part of the investment impetus came as a bet that the stigma against subdividing territory was weakening in the shadow of the Iraq war. Buoyed by RED’s positive reception in the news, they announced plans to bring Silicon Valley’s “spirit of innovation” to Honduras in 2011. Just a few months later they had a memorandum of understanding with the government.

And yet the RED system never took off. In mid-2011, the Honduran Supreme Court struck down the bill 4-1 out of fears that it threatened Honduran sovereignty.

In 2013, Honduran officials came up with an alternative model: the ZEDE, a Spanish acronym for Zone of Economic Development and Employment—pronounced “ze-dey.” In 2016, the ZEDE law passed with the support of 78% of Congress, and two ZEDE contracts were distributed: one on the mainland called Ciudad Morazán, funded by a massive Honduran consulting firm. And the other, in 2017, to Próspera.

When Próspera first started, it purchased a 58-acre plot of land for $17.5 million, and started to build some experimental “beta-buildings” on site, testing out their futuristic approach to architecture. By 2021, their territory had expanded to 1000 acres, mostly on the island of Roatan. Their executive team was made up of various city-builders with experience in the special economic zones of Dubai, and Sandy Springs, Georgia. Their business charter cobbled together various tech-forward legislative approaches, like e-residency for digital nomads, taken from Estonia, and 3D land rights, with digital records stored on the blockchain. It also has the lowest tax rate in the world.

The Pristine Bay Beach Club is a three-story building at the center of Próspera—a stucco mustard entry hall that’s part of a 1000 acre expansion it took over from investors in 2021 betting Roatan would become the next Tulum. It overlooks a prime sliver of the white sandy beach along the coastline that’s yet to be treated for insects, so it’s infested with sand flies that kept biting at people’s feet. Inside, there’s a coworking space, with high-speed internet provided by Starlink, a conference room, and a fully equipped gym. Outside, an infinity pool, beach chairs, and a shaded platform, with cold plunging tanks as far as the eye can see.

It was here that I met Niklas Anzinger, a podcaster and startup founder who helped start Vitalia in 2023. Anzinger speaks in a mild German accent, watered down from years of working in the Valley, and he’s built like an out-of-season hockey player with thick long hair. In 2022, after reading a prospectus on Próspera by the rationalist blogger Scott Alexander, Anzinger came to Roatan to find a group of real estate developers sympathetic to building on the network state ideal. Anzinger sees himself as an intellectual and an economist, but his muscular hands and baggy cargos tell a different story. Anzinger is a man who’s spotted opportunity on what seems like a nascent plot of arable land, and has gotten to work installing the pipes and the septic tank. “I’m an entrepreneur so I’m not attracted to doing pie-in-the-sky things,” Anzinger said. “I want to do things that actually succeed. And then I came here and felt this visceral ‘wow.’” He drummed his hands in a wide circle as he was speaking. “Like, this is real. The tower is real.”

A few months after his first visit, Anzinger moved here with his wife Victoria to launch his venture capital firm, Infinita, “the startup city VC.” Together, they purchased a unit in the forthcoming Duna Residences, designed by the late architect Zaha Hadid, and began making investments in the few startups that had set up shop on the island.

After conducting a podcast interview with Sebastian Brunemeier, a 28-year old biotech entrepreneur known as a maverick in the longevity field, Anzinger was convinced that the industry with the most to gain from Próspera’s style of “legal innovation” was longevity biotech. “I didn’t know longevity was even a possibility until a year and a half ago,” Anzinger admitted. “Próspera is the only place in the world where this type of legal innovation is possible,” Anzinger told me. “So that’s how the two came together.”

The oft-repeated headline of Próspera’s approach to “legal innovation,” is that companies operating within its limits can be legislated according to whatever set of rules they choose, including ones of their own making. While this is partially true, it’s more complicated in practice. Próspera’s Technical Director Jose Colindres—who you might think of as Próspera’s mayor—explained that there are two sets of rules that govern business activities in Própera. One for businesses that operate within the zone’s ten “regulated industries,” like medical services, financial services, construction, agriculture, and so on. And the second for everyone else, like food and beverage operators, who operate according to American common law by default.

The difference is that companies in the “regulated industries” need to do what’s called a “regulatory election,” where they propose a set of their own regulations to Próspera’s council, a team of mostly-American investors based in Arizona, which is controlled by the zone’s primary investment group. Only two companies have approved optimal regulations so far, Colindres told me—Minicircle, who ran the island’s first clinical trial for a nascent gene therapy, and the GARM Clinic, the island’s main longevity medical hub.

Once an optimal regulation is passed, any company can elect to use it. The idea is that, once a baseline of “optimal regulations” are established, it will streamline the process of setting up businesses with “unconventional” needs. The onus of calculating risk is left to the island’s insurance markets, and damages for medical malpractice lawsuits are capped at $250,000, a quarter of the average trial rate for medical suits in the United States.

On my first day at Vitalia, I checked in at the “Bored Apes Yacht Club,” an offsite hotel so-nicknamed after the NFT collection, and went back to the beach club to learn what all this meant in practice. Drifting past the paper signage in the conference room with slogans like “Review Holistic Systems” and “Acquire the Best Land for Your Needs,” I arrived at the biohacking lab where I met Jeffrey Tibbets and his team at a bionics company called Augmentation Limitless. Tibbetts, who goes by the alias “Cassox,” is a registered nurse and an early pioneer of the “grinders'' movement—a community of biohackers known for implanting non-medical devices, such as wifi routers and lighting fixtures that glow under tattoos, into their bodies. If you google his name, the first link is an MTV True Life story from 2016: “Is Cassox still experimenting with smart drugs?”

“We're kind of like a piercing parlor, or a tattoo parlor, in terms of actual risk,” Cassox said, “because the implants we're doing are not equal to deep surgeries for medical devices, like pacemakers. So we're taking an approach of, ‘let's find the closest thing that matches the risk profiles of what we're actually doing, and propose that that’s how we should be regulated.” The main product they were selling in the lab was a pill-size crypto-wallet activated by NFC, a style of wireless chip reader often used in key fobs. It’s designed to be lodged between the thumb and index finger. When I spoke to Tibbets, he said they’d already done about twenty implants during their stint at Vitalia. Operating in Próspera presented an opportunity for Tibbets because the “Optimal Regulation” system allowed them to sidestep the “clunkiness” of American legal categories that prevent non-medical surgeries. Tibbets’ plan in moving to Próspera was to spawn an entire biohacking industry, starting with a fabrication lab and a physician-monitored medical clinic.

Another “legal innovation” is Próspera’s policy of medical reciprocity. Próspera claims to be the first place in the world to allow doctors with valid medical licenses from any developed country to practice there, a departure in policy from that of countries like the United States or Canada, where you’ll meet cab drivers or other service workers who have had to abandon their medical credentials because it wasn’t recognized by their host country. The main medical hub on the island, called the GARM clinic, offers a “time-share” program called ‘WeTreat’ modeled on the rental model of WeWork. Patients and doctors can fly down to receive drugs or therapies that aren’t available elsewhere. Take, for example, a $25,000 telomere treatment developed by MiniCircle that rejuvenates the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, supposedly to reduce muscular recovery time so you can make outsized gains in the gym.

Próspera also has 100% drug approval reciprocity, meaning that if a drug has been approved in another developed Western country, it’s also approved in Próspera. The idea is to stop repeating medical research for the sake of satisfying a national regulatory authority, like the FDA, which according to critics like Sebastian Brunemeier, the longevity entrepreneur who initially inspired Anzinger, block certain drugs for political reasons. “Monopoly regulators are inefficient and corrupt,” Brunemeier told me on the couch of his villa’s veranda by the pool. “There are a lot of drugs that should be available that are not and they're approving drugs that should not be reimbursed by insurance, just because of political connections with the pharmaceutical industry.”

Anzinger set up his VC firm in Próspera to sidestep these inefficiencies. His investment thesis is about modifying societies’ “base layer,” the legal, and so-called “regulatory operating system,” on top of which things like housing and infrastructure are built. According to Anzinger’s thesis, society is struggling to build those things because the base layer has been hijacked by corporate corruption and the slow build-up of regulation that have made it unnecessarily expensive to build. “The main barriers [to innovation] are offline,” Anzinger told me. “As in, how do we get the science and technology that we have actually into production?”

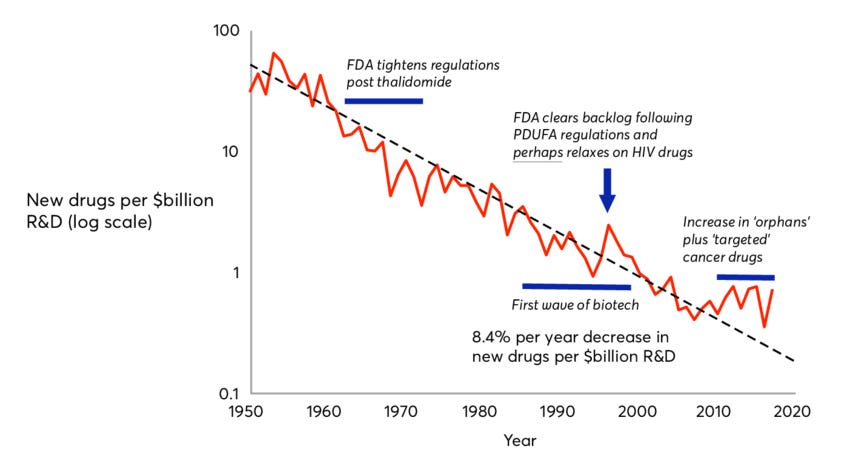

He said the drug approval process in the US is a prime example. The current cost of getting a new drug to market is roughly $2.3 billion, with an average ten-plus year time horizon to get a new therapy approved. It's getting slower and more costly over time, Anzinger said—a pattern that’s explained by “Eroom’s law,” the inverse (and anagram) of “Moore’s Law.” The idea is that the inflation-adjusted cost of developing a new drug roughly doubles every nine years, despite advances in technology. (Though the validity of the principle is disputed.)

The thesis is that some companies (and places, like Próspera) can help change this dynamic. Companies otherwise hemmed in by regulation, he claims, can shave 90% off their time-to-market. The gene therapy company Minicircle, for example, claims that the cost of running a clinical trial in Próspera is less than 1/1000th of what it would cost in the United States. Part of the cost savings is a reduction in overhead and fewer safety requirements. But it also has to do with patient recruitment, a central cost for most pharmaceutical companies. Minicircle sources and pays its prospective patients with NFTs.

Vitalia, in this sense, is an exercise in recruitment—courting researchers, startup founders, investors, and technologists to build up the value of Próspera’s land by taking advantage of the lax regulatory regime. If you can convince enough people to move there, buy homes, and start businesses, you can, the logic goes, build Roatan into the next Hong Kong or Singapore; case studies in the global proliferation of para-national “zones.” As Quinn Slobodian explained in Crack-up Capitalism, there are over 5,400 such zones around the world, some no bigger than a factory or warehouse. All are more or less engaged in what he calls “micro-ordering the global polis”—puncturing holes in the jigsaw puzzle of nation-states while attempting to undermine the system itself.

Próspera, as the largest zone to gain a foothold in the Western hemisphere, is its most fortuitous instantiation. Besides a basic commitment to laissez-faire capitalism, the philosophy guiding this process of political perforation was perhaps best articulated by Peter Thiel in 2014, during a lecture at the Seasteading Institute. If in 1945 there were about 45 countries in the world, he said, and today we have about 200, how many countries will exist by 2050? Will it be greater than 200, less than 200, or exactly 200? The three different scenarios give you three different futures of the world, and three different degrees of relative “freedom.” What would the world be like, for example, in a future where there are twenty countries, or two, or one? How about 1000?

The pop-up-city-conference started in January, and was punctuated by four separate events where the population temporarily spiked. The paupers are your average smart-watch wearing tech workers seeking a career change, science researchers looking for funding, and ex-crypto founders self-styling as longevity entrepreneurs. The first-class are the funders, founders, tech teams, and crypto-rich, all of whom stay off site at the villas. The first question people ask you, as if you’re riding up a chairlift together, is whether you’re there for the network state stuff or the longevity stuff.

The cultural topography reflects the split—a confluence of competing agendas, set by the funders and luminaries who bestow the event with legitimacy in exchange for a commercial shadow. On the tech side, there’s Balaji Srinivasan, Naval Ravikant, the founder of AngelList, and Peter Thiel, all of whom have invested here and serve as the communities’ de facto philosopher kings. And then there are the longevity luminaries like the English gerontologist Aubrey De Grey, and the billionaire biohacker Bryan Johnson, famous for injecting packets of his sons’ blood plasma and strapping himself to an erection monitor that keeps track of his boner activity while he sleeps.

My introduction to longevity, like that of many others, started with the strange rabbit hole that is Bryan Johnson, a regular client of the GARM clinic, whose “blueprint” method—which covers everything from diet to sun exposure to a wide litany of experimental drugs—is used as the basis of Vitalia’s daily breakfast. Learning about longevity through an encounter with Johnson is a common experience, according to Mark Hamalainen, the longevity educator who’d helped me gain admission to Vitalia. “Bryan Johnson is a divisive character,” he said. “If all you see is his Twitter posts you’re not going to actually understand his philosophy. He’s just trying to get people to pay attention and hope that some percentage of them actually dig a little deeper.”

When I spoke to Dr. Nir Barzilai, the founding director of the Institute for Aging Research at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, he put things somewhat differently: “Bryan Johnson takes a lot of the oxygen in this field,” he said. Barzilai is a chatty Israeli researcher who’s been proselytizing longevity for many years. “I'm often interviewed about him and I'm kind of antagonistic,” he said, because Johnson’s biohacking experiments are dangerous, unverified, and capture a lot of attention. “What would happen if Bryan Johnson dies this year?” Barzilai asked. “How is it going to affect the field?”

The differing attitudes represents a general cleavage within the industry—on the one hand between people like Hamalainen who advocate for radical life extension, even immortality, and on the other, people like Barzilai who think that a slow, but measured approach to aging can extend the human lifespan up to around 120 years.

At the heart of the new science is a basic theory that sees aging as a kind of root-cause “disease,” driven by the acceleration of twelve interconnected processes known as the “hallmarks of aging.” Genes become unstable, stem cell production slows, nutrient sensing becomes deregulated, and so on. As these processes accelerate with time, they result in illness and death. Longevity drugs target these “hallmarks” and attempt to slow or reverse them. Some researchers focus on animals, like sperm whales and naked mole rats, which exhibit delayed aging patterns, or “negligible senescence,” and attempt to isolate the chemistry of their aging strategies for reproduction in humans. Other approaches include finding small molecules in plants and other materials, and converting them into drugs that target specific hallmarks and attempt to reverse or delay their expression.

Traditional gerontologists like Barzilai are mostly focused on the latter approach—raising money for drug research. Then there are more extreme measures, the “engineering approaches,'' that sidestep drugs altogether. Full body replacement, brain grafting, cryopreservation, cloning—all of these appear as technical problems-to-be-solved on Hamalainen’s “longevity roadmap,” a PowerPoint presentation published on his company's website. “DNA is basically software,” Hamalainen said during a presentation at Vitalia. “So eventually, you can imagine us just getting software updates.”

Despite approaching the field in different ways, Hamalainen and Barzilai both confess to having spent most of their careers being laughed out of rooms. But in the last two years in particular, amidst public reactions to Covid and growing policy attention to the problem of aging populations around the world, there's been a sea change in the way people think about longevity, and how they’re investing in it. Insiders, like Barzilai, say the incoming wave of longevity solutions is generating a once-in-a-generation “gold rush.”

“If we even expand healthspan by a couple of years,” Barzilai said, “it's going to be a savings of $38 trillion a year, or $360 trillion in the next 10 years.” He cited a study from the London School of Economics. “The CDC is showing that people who die after the age of 100 have a third of the medical cost of people who die when they're 70,” he said, because centenarian bodies reach a form of aging-statis that can remain in place for decades. “So it's really important. There is no other option for us.”

The energy at Vitalia reflects this shift in fortune: a group of people previously relegated to the shadows, suddenly commanding a massive volume of resources and attention. In the last two years alone, Saudi Arabia committed $100 billion to longevity research through an organization called the Hevolution Foundation. Mubadala Capital has committed $36 billion. Pfizer, Novartis, and Merck have all begun investing in longevity-focused firms. And Altos Labs, a longevity research company focused on cellular rejuvenation, recently raised over $3 billion as part of its initial funding, with a rumored $2 billion from Jeff Bezos alone.

Even more “radical” approaches to longevity have attracted significant funding. At Vitalia, I met Petr Kondaurov, a Russian entrepreneur, who successfully raised $500,000 to study the mechanics of head transplantation on living mice. “Head transplantation is a very old idea in transhumanism,” he told me. With time, he hoped to adapt his research for humans.

In the midst of the conference I met Travis Bresa, an undergrad anthropology student at Oxford University with a thick mane of curly red hair, who’d come to Vitalia as research for his thesis project on transhumanism. Right before Vitalia, he told me, his advisor was in touch with He Jiankui, the rogue Chinese biophysicist known for creating the world’s first so-called CRISPR babies; a stunt that earned him three years in jail for operating without a review board and a reputation as “China’s Frankenstein.” According to Bresa, Jiankui was invited to speak at Vitalia but decided to turn down the opportunity. His reason: “because it was too sketchy.”

And yet VitaDAO, the primary sponsor of Vitalia, also has funding from Pfizer, an unusual bedfellow for a group with such a liberal approach to “innovation.” Paolo Binetti, a deal flow coordinator for VitaDAO, explained how the partnership arose. Pfizer became interested in VitaDAO after the company made a $1 million investment in a single startup called Turn Biotechnologies, Binetti explained, an unusually large investment for an unknown group. Pfizer was interested in learning how a small minnow, funded by crypto, “could enter the game of biotech startups with massive funding.” He said, “We did it on purpose for attention.”

VitaDAO’s business model is what Binetti calls a “venture philanthropy;” a concept coined by MIT professor Andrew Lo in 2019, modeled on the experience of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF). When the CFF started, they invested in a combination of basic research and practical applications, and eventually discovered how Cystic Fibrosis worked. In 2012, the research led to the development of a revolutionary drug, and in 2014, CSF sold the drug’s intellectual property rights to a company called Royalty Pharma for $3.2 billion. CSF’s initial investment was $150 million, Binetti explained, “so you make the difference.” And that’s the idea of VitaDAO, but for longevity—to help solutions get out of the lab and into humans.

At Vitalia, the allure of crypto looms large. “The crypto world already works like a proto-network state,” a Vitalia attendee told me. “You had one of the largest wealth creation events in world history in the last ten years,” but in places like the United States people think crypto is dead. It’s not.” (As of November 2024, the price of bitcoin had reached all time highs.)

“Vitalik Buterin is one of the richest people in the world,” said James Sinka, a founder of OrangeDAO. “If you ask him to wire you money for your startup it’s not gonna happen. Ask him to transfer you some ETH and you just might get it.”

After sunset, the crowd dispersed and reassembled at a bar nearby where I was told there would be dancing and karaoke. The air abuzz, I watched as the bonfire refracted on the dark of the ocean and people ordered drinks delivered by the Garifuna servers. As the night wound down, Hamalainen and his team of longevity fellows began to spool out on the dancefloor. They carried microphones in hand, forming a semi-circle around the projected screen. A familiar harmony of high strings and synth began to play, followed by the voice of Mr Hudson and Jay Z while the snare began to kick. Soon the group's eyes were closed and they screamed the chorus like a prayer into each other's open mouths. I could hear it echoing down the beach: “Forever young / I wanna be forever young.”

The logic that underpins the medical system in Próspera is what’s known as the “right to try”—the idea that certain patients should be able to access treatments not yet approved by regulatory agencies. Dr. Jess Flanagan, a medical ethicist at the University of Richmond who attended Vitalia in January, argues that the right to try allows patients to sidestep the “paternalism” of the Western medical system, and in particular, the FDA, which restricts access to certain drugs on the basis that regular people can’t sufficiently evaluate medical risk.

Próspera’s representatives at Vitalia continued to claim that the organization is “conservative” when it comes to approving new treatments, meaning it won’t approve anything that poses risk to its business interests. But Próspera is also positioning itself as an experimental hub for medical tourism. To understand what this meant, I spoke to Josh Mann, a drug scout for Pristine Regenerative Nexus (PRN), the GARM clinic’s parent company, whose job is focused on sourcing new longevity treatments to offer on the island.

When a new treatment is proposed as a potential offering, he explained, it’s reviewed by PRN’s internal review board, who decide whether they want to approve the treatment at all, and if they do, it’s kicked back out to Próspera’s external board for additional review. “So there's two levels of checks and balances,” Mann said. “Approval really depends on how much information or data the company has.” PRN’s regulatory board, he said, currently staffs a former FDA Deputy Director, and a team of external consultants, each with 20 to 30 years experience advising companies on the regulatory process in the U.S. “There can be no deaths,” Mann said. “It would completely destroy what we’re building.”

Mann considers Próspera’s review board to be more “nimble” than the FDA. Partly, that’s because a smaller organization with fewer cases can move faster. But it also has to do with specialization. “We're finally at a point where we're actually seeing personalized precision medicine,” Mann said. “The FDA was designed to approve, like, a medical device with a piece of metal on a joist, or a small molecule. Now there are things like gene therapy, or diagnostic genomics. So [regulating new medical solutions efficiently] requires keeping up with technology. And this is where I don't necessarily blame the FDA.” he said. “The science is advancing so rapidly.”

When I asked Mann whether, for example, they would approve the head transplantation research proposed by Petr Kondaurov, he said that PRN is not currently set up to facilitate testing with animals. Ultimately, that would be a Próspera question, he said—the final answer on just about everything. When I asked Próspera’s Technical Director Jose Colindres about it, he said that if the testing was focused on mice, it would likely be approved.

This raises a number of difficult questions for Próspera’s fledgling “proprietary” government: What are the risks of running a libertarian city-state like a startup, especially when it comes to medical safety? And is “proprietary government” a disaster waiting to happen, as some claim? Does the insurance market actually work as a meaningful stopgap to dangerous behavior?

The current condition of Próspera vis-a-vis the Honduran government might be a good place to start. Próspera is in the midst of an ongoing legal battle with the Honduran government over the government’s attempt to repeal the ZEDE law which granted its ability to operate. In September, the Honduran Supreme Court ruled that the ZEDE law was unconstitutional, and announced an immediate prohibition on the creation of new zones. Honduran court spokesman Melvin Duarte told Reuters the decision also implies that existing ZEDEs will be declared illegal, the details of which will be clarified in an “explanatory addendum.” But with a presidential election scheduled in Honduras for November 2025, and Donald Trump in the White House, the tides of anti-ZEDE sentiment may shift. In Trump’s ‘Agenda47,’ for example—the policy manifesto he’s currently ‘touring’ around the US—he proposes the creation of ten chartered ‘Freedom Cities’ on ‘undeveloped’ Federal land. If the Republicans pursue this model on American soil, how will it impact similar projects internationally?

Of course, the recent Supreme Court decision is not the first time that there’s been a legal battle between Prospera and the Honduran government. In 2021, Próspera Inc., the zone’s primary investment vehicle, which is technically a US corporation, brought a case to the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, or ICSID, seeking more than $10 billion in damages from the Honduran government. The amount is roughly equal to a third of the country’s GDP.

The basis of Próspera’s claim, said Próspera’s Technical Director, Jose Colindres, who is currently under investigation for treason, is that when the ZEDE law was passed, measures were taken to ensure that the law wouldn’t be swept away by political instability. After all, he said, the ZEDE law was put in place by a government that gained power during a military coup. The stability mechanism was a constitutional law requiring a congressional supermajority to make any changes to the ZEDE law, and an international treaty guaranteeing a “legal stability period” of a minimum fifty years. “But then we got our crazy radical socialist communist government,” he said, referring to the current Honduran President, Xiomara Castro, who came to power in 2022 and began gesturing toward repealing the ZEDE law. The $10 billion amount is based on a multiple of the initial investment: the $500 million slotted for investment in the first five years of Próspera’s existence multiplied over the next fifty.

In response, President Castro has started taking steps to withdraw Honduras from ICSID, sidestepping arbitration altogether. In March, eighty-five leading economists published an open letter calling the withdrawal a “critical defense of Honduran democracy.” The group, which includes people like Greece’s former finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, and Colombia professor Jeffrey Sachs, argues that “Honduras presents a powerful case of corporate abuse through the ICSID system.” The ZEDE law allows “private cities [to] operate almost without regard for labour, environmental, or health regulations,” they say.

Within Próspera, however, opinions vary. Under hushed voices, Vitalia attendees pointed out that, according to polls, only 5% of the Honduran population are in favor of the ZEDE law, while 40% are against it. When I asked Niklas Anzinger about this, he brushed it aside as “absurd” with a gripe about the accuracy of polling. He admitted, however, that ZEDEs were unpopular under the last government, but he chalked up this attitude to the normal vacillations of political sentiment. “Politicians in the capital city rile up the population that are not here on Roatan and are not seeing a benefit,” he said. “Within five years, we’ll add up to 95% foreign direct investment just in this country.”

President Castro, has made antipathy to ZEDEs a central part of her government's platform. The slogan “no to the ZEDEs” was a central facet of her electoral campaign, so shortly after her inauguration, the Honduran Congress voted to repeal the ZEDE law, spurring the aforementioned court case.

Castro’s anti-ZEDE argument is that Próspera, and other organizations like it (there are currently three ZEDEs in Honduras), are merely the modern version of the mining and banana enclaves that dominated Central America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These companies compromised sovereignty all over Central America, and Honduras in particular, she has argued, operating like quasi-nation states with tax exemptions and policing restrictions. As Castro told the U.N. General Assembly in 2022: “every millimeter of our homeland usurped in the name of the sacrosanct freedom of the market, ZEDEs, and other regimes of privilege was irrigated with the blood of our native peoples.”

Castro’s central fear is that if action isn’t taken to curb the power of organizations like Próspera, ZEDEs "will later become free states, independent of [political] process." It’s a legitimate fear given the ambiguous language of the ZEDE law, which makes it possible for ZEDEs to expand their territory up to 35 percent of the country, according to a UN report.

Currently, there are seven geographic “departments” within Honduras that are eligible to join ZEDEs, most of which are low density zones on the coast. Because ZEDEs operate like a local government, these zones can choose to be incorporated into the legislative structure of a ZEDE, which is what enabled Próspera to expand from five to 58 acres during its first stage of development to an additional 1,000 acres in Pristine Bay during the height of the pandemic. They didn’t “buy” the land, it was simply incorporated into the zone legislatively. All individual homeowners in the villas were able to opt in or out, Colindres explained. All of them opted in.

Representatives from Próspera claim that they have no ambitions to expropriate land. As CEO Erick Brimen told Reason in 2021, “Próspera specifically cannot receive expropriated land into its jurisdiction, period. End of story.” However, Próspera’s most recent venture—plans to expand onto the mainland in a town called La Ceiba—challenges this claim. Próspera wants to build La Ceiba, now mainly abandoned roads and weather-worn clapboard homes, into a manufacturing hub, on the model of Shenzhen, framing the project as part of a shift in American supply chain strategy toward “nearshoring.” A recent press release about the expansion explained that the city-scale development will soon be home to “more than 100,000 workers and 50,000 residents.” Over the next ten years, the release projects that total investment in La Ceiba will exceed $5 billion.

Part of the rationale is that Próspera is a “platform” for governance that can be replicated and built upon, not just a government in a specific location. As Brimen stated in his presentation, “governance is the world’s largest industry, but 5% of governments control 80% of the market, 90% lose money, and 81% of citizens are dissatisfied with the service.” Próspera’s premise is that better governance and rule of law can fundamentally change economic conditions by attracting more investment and making it easier to do business. It’s a principle taken straight from the charter cities manifesto proposed by Paul Romer in 2009.

All of Romer’s arguments are baked into Brimen’s pitch. In his presentation, Brimen cited that Honduras is ranked 154 out of 190 countries in “contract enforcement” by the World Bank, a measure commonly used as an indicator of the ease of doing business. It also has a 70% poverty rate, the 5th highest murder rate in the world, and an unstable political system widely known as being corrupt and dysfunctional. Meanwhile, Próspera is now ranked 9th globally on the ease of doing business according to Ernst & Young. And it continues to attract investment—a signal of its supposed path to continual success.

Residents in the areas surrounding Próspera, like those in Crawfish Rock, a small fishing village on the outskirts of Próspera, are divided. On the last day of the conference, I walked along an unkept stretch of sandy beach to Crawfish Rock, strolling past the mangrove trees and anti-ZEDE signage hung on the palms. Standing by the ocean in the early evening, I spoke to Henrik Minten, who grew up in Crawfish Rock and runs a transportation company there with his brother. Pointing to one of the houses nearby, a small wooden building on stilts, he said, “this lady here is one of the big ZEDE fighters. And another lady down there. That all started with two ladies. It’s not the whole community because most of the community is employed by Próspera.”

That said, he went on, “a lot of people are scared about the ZEDE law.” Minten thinks that people in the community are mostly repeating what someone else told them, and that “what Próspera did was good.” He explained that they’ve already paid a scholarship for about thirty kids and that they gave the whole community water during the pandemic.

The details of these philanthropic efforts, however, tell a more complicated story. Prospera did provide water to Crawfish Rock for about three years, but villagers were charged for the water for most of that time because the organization doesn’t “believe in charity.” Crawfish Rock community leaders also claim that the organization used its dependence on the water system as a way to squash opposition to the ZEDE among residents. The conflict came to a head in 2021, when Prospera’s leadership heard that efforts were being made to restore the community’s old water supply. Interpreting these efforts as a signal that the community no longer wanted Próspera-ZEDE sourced water, Prospera issued a letter threatening to shut off the water if community leaders didn’t respond within thirty days. A month later, the taps in Crawfish Rock ran dry.

As Lorena Webster, another resident of Crawfish Rock, told Reason in 2023, the fear is not about what’s happening right now, but what might happen in the future. “Maybe at the beginning it will benefit us because they may give us jobs,” she said, “but in the future, the laws give them the privilege to take our land"—though nobody from Próspera has ever threatened to take her home or even offered to buy it.

Attitudes among the American foreign policy establishment are split. On one hand, President Joe Biden joined a group of thirty Members of Congress to denounce Próspera’s use of ICSID to “bully” Honduras. But on the other hand, the U.S. State Department voiced concern over the Honduran government’s decision to repeal the ZEDE law, arguing that it “contributed to uncertainty over the government’s commitment to investment protections.” Laura Dogu, the American ambassador to Honduras, stated that efforts to repeal the ZEDE law “sends a clear message to companies that they should invest elsewhere,” which undermines efforts to develop the Honduran economy. A weaker economy means more economic migration, the logic goes, meaning more public spending to protect the border as opposed to private investment directly in the Hondruan economy.

With a presidential election in Honduras set for 2025, Próspera’s future is still uncertain. Will regime change install a government permissive to Próspera, and other ZEDEs, leaving the door open for expansion? Or will Castro, who has called for a "refounding" of Honduras—an overhaul of the constitution and a nationalization of the country’s energy sector—succeed? If Castro wins, and Próspera’s legal defense is thwarted, might the conflict come to arms? It’s hard to say, but the Israeli security guards patrolling the perimeter suggest that Próspera is taking security very seriously.

The last day of the conference, I woke up early and found myself cold-plunging on the veranda, coached on the Wim Hof method by a bearded German man sunbathing in his underwear. I stood above the giant infinity pool that was conspicuously empty throughout the entire week, looking out at the ocean.

At the closing ceremonies of Vitalia, a crowd had gathered on the golf course, surrounding an elephant-sized, papier-mâché skull, painted in red and yellow like a Mexican calavera, the ornamental sugar skulls made famous by the region's most consumable celebration, Dia De Muertos.

The organizers who spent the week assembling their creation at the beach club may have seen the skull as a symbol of memento mori, their plans to burn it a reflection of their intention to burn away death itself. But what they probably hadn’t considered, besides the fact that we weren’t in Mexico, was that the making of calaveras was not an indigenous tradition, as the Spanish colonists had once claimed, in an attempt to sell it as “authentic” to foreigners. It was a tradition that had started in the 18th century as a form of ritual protest, converting the skull, a symbol of the Mayan and Aztec traditions, into a death offering, made colorful and optimistic, with the raw material in whose pursuit the colonist had remade the region and killed millions in the process—sugar, the crop of death.

Standing by the 19th Hole, a driving range just off the golf course, I watched and listened as the organizers fumbled to light the giant skull with bamboo torches. A recent German college graduate was speaking about his plans to start a new university on the island. A Rhodes scholar turned-startup founder was discussing her plans to create another network state event in Georgia. I could hear grumbles about the male pheromone trial that had taken place earlier that day, where male participants were asked to rub gobs of semen on their neck to evaluate women’s motor skills after they hugged them.

I started thinking about Jacques Derrida’s famous pronouncement, in the aftermath of 9/11, that as our ability to think of the world as a coherent, controllable object begins to crumble, “there is no world, there are only islands.”

It took a long time for the head to catch fire, so people started pouring kerosene on its red and yellow ears and the nose. A group of devotees danced around the flame in baggy pants, their bare chest an homage to the ceremony's “pirate” theme. John Coxen, the so-called pirate who Roatan’s main city is named after, was a high-born British lad, once a starling commander of the English fleet. At first, he’d been contracted to pillage the Spanish armada, and only after the treaties changed, did he become a “pirate,” a thief. With a British flag and a piece of paper, Coxen had been a privateer, a representative of the English navy; without these things, Coxen was a beast—a buccaneer, hoarding gold he’d stolen from a nascent system of sugar production, inscribed on the region by one of the fledgling nation states he no longer called his home.

The thwack of golf balls echoed in the distance, and soon the flame rose to consume the skull. The papier-mâché started to release and flew like lanterns across the lawn. It reminded me of the origami boats we’d set on fire earlier in the week and launched into a backyard swimming pool. Hamalainen had told us that when Alexander the Great came to conquer an island he’d force his men to burn their boats so that they knew from the outset it was do or die. That’s the condition we face now, he said, “either we end death or we die.” So we lit the boats on fire and set them into the pool, then fished them out a few moments later when they started falling to the bottom.

What a bunch of grifters. Good story.

I stayed there for 2 months during Vitalia pop-up city and produced a documentary featuring Balaji, Patri and others.

https://startupsociety.film