Divine Violence and the End of Pain

What can René Girard, Yukio Mishima, and the original Luddites tell us about Luigi Mangione's violent act?

“Left-wing or Right-wing, I’m in favor of violence”

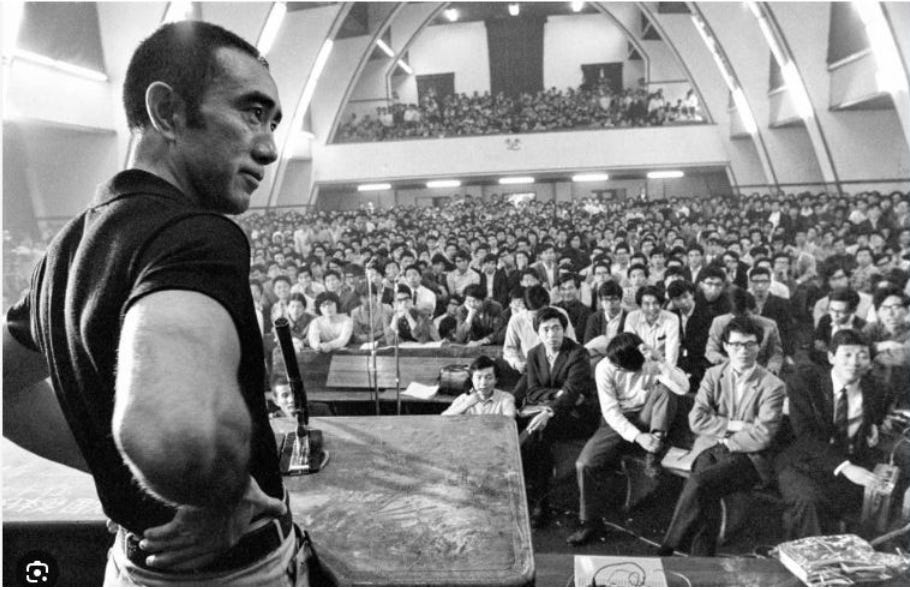

—Yukio Mishima, Debate at the University of Tokyo, 13th of May, 1969

A few years ago when I was a visiting scholar at Johns Hopkins University, I spent Thanksgiving in the Baltimore suburb of Roland Park where Luigi Mangione graduated from the Gilman School as valedictorian. I was struck by how serene, quaint and architecturally pleasant the neighborhood was, and its resemblance to the idyllic scenes of American suburbia I’d seen in many films. It stood in stark contrast to where I was subletting a room not too far down the road in Hampden, near what I assumed was an addiction clinic for opioid addicts. Not being able to drive, and much to the shock of some colleagues, I often walked to the university and sometimes into the city. Some mornings when walked past the clinic, I would briefly exchange pleasantries with some patients congregating outside chatting and smoking. They seemed a very heterogeneous group of people, and not entirely conforming to the popular perception of drug addicts. I surmised that many had come to addiction and immiseration through the pharmacological route, through medication mis-prescribed by unscrupulous doctors for debilitating pain. I’ve only briefly experienced the type of pain for which such medication is necessary, after a minor surgery, so I can well understand how more constant, intense and unabating pain could lead to desperation for respite, or the mere ability to function day to day.

Pain is something that psychically transported Mangione from the plush upper-class surroundings of Roland Park to the wretched realties of Hampden and other parts of the city—that is to say, from one insulated and exclusive American existence, to one more exposed, vulnerable and universal. The manifesto which Mangione wrote expresses opposition to the parasitism of the health insurance industry, while on another level conveying some degree of loyalty to authority. He was educated at Ivy League institutions, worked in the tech industry and seemed to have been committed to physical fitness, self-improvement and self-actualization. It’s doubtful we will discover his actual motivations, and its likely there will be a concerted attempt to moderate them. Yet we know that a marked change in his personality and fortunes occurred when he began to suffer from debilitating chronic pain from a spinal injury, with many speculating that he experienced callous treatment by America’s obscene and byzantine health insurance system, and its recent turn towards Artificial Intelligence to assess claims.

In the perplexing case of Mangione we find ourselves confronted with two perennial themes—Pain and Violence, two fundamental features of human experience that are related but distinct, which we scarcely seem to fully understand. They nonetheless hold the key understanding the mollifying nature of modern technological society, and why it increasingly drives men toward acts of extreme retribution—and by looking at a rather odd collection of sources which will include, amongst others, Ernst Jünger, Peter Thiel and Yukio Mishima—we might be able to better understand the nature of the problem.

In his prescient essay On Pain (1934), Ernst Jünger wrote of how an emergent technological society sought to abolish pain and inculcate boredom and complacency, even while demanding greater personal sacrifice to a ruthless economic logic. For Jünger it was a shift from his vaunted aristocratic virtues of honor, pride, and duty to a bourgeois worldview of bare life, self-preservation at all costs:

The growing objectification of our life appears most distinctly in technology, this great mirror, which is sealed off in a unique way from the grip of pain . . . . We are too deeply immersed in this process to comprehend it to its full extent. If one gains even a little distance . . . the claim on life becomes more visible.

For Jünger technology was embodied in the unreality inculcated by the dominance of the photograph (a precursor to our more advanced image culture) which functions as an “expression of our peculiarly cruel way of seeing . . . a kind of evil eye, a type of magical possession.” Drawing on his experience of the First World War—a technological war which brutalized and exterminated an entire generation of young men, leaving countless others maimed physically and psychically—Jünger proposed that the future would be determined by the men who could gain mastery over “pain,” and thus over technological anomie. Pain is the

only measure promising a certainty of insights. Wherever values can no longer hold their ground, the movement toward pain endures as an astonishing sign of the times; it betrays the negative mark of a metaphysical structure.

He continues:

The amount of pain we can endure increases with the progressive objectification of life. It almost seems as if man seeks to create a space where pain can be regarded as an illusion, but in a radically new way.

Despite clearly once being in thrall to the ideas of tech-utopians and despite being fully immersed, like we all are, in this virtual sham existence, perhaps Luigi Mangione could no longer regard his very palpable and excruciating pain as illusory in the accepted palliative ways. Perhaps it began to assume a state conducive to certain insights capable of jolting him from stupefaction into action. In his will to transgress the law, putatively in the service of a higher Law, this brutal assassination ties into what philosophers on the left and the right have long acknowledged forms the basis of “Divine Violence.”

Franco Berardi’s Heroes: Mass Murder and Suicide (2015) attempted to inform us of the perturbing effects of technological alienation on the contemporary male subject. The epic hero, Berardi maintained, subjugated nature through strength of will and courage, imposed order, fended off chaos, and founded nation-states. Yet this epic form of heroism has, since the advent of technologies of mass communication in the 20th Century, receded as “the complexity and speed of human events overwhelmed the force of the will”:

When chaos prevailed, epic heroism was replaced by gigantic machines of simulation. The space of the epic discourse was occupied by semiocorporations, apparatuses for the emanation of widely shared illusions. . . .Here lies the origin of the late-modern form of tragedy: at the threshold where illusion is mistaken for reality, and identities are perceived as authentic forms of belonging. It is often accompanied by a desperate lack of irony, as humans respond to today’s state of permanent deterritorialization by enacting their craving for belonging through a chain of acts of murder, suicide, fanaticism, aggression, and war.

While Berardi’s analysis is somewhat compelling, his call to be conscious of the “simulation at the heart of the heroic game” through the use of “irony” is not at all convincing. The reason for this is generational. Berardi belongs to a cohort of thinkers for whom irony served as the supreme form of radical dissent, or as Richard Rorty suggested, a key concept of “liberal hope” that fosters understanding within democratic societies. The current moment is, however, one oversaturated with irony. It is an irony evident even in its rare expressions of earnestness. But amidst the chaos and detritus of contemporary digital culture, its profusions of “content” and masses of data, its near compulsory principles of self-abjection as self-expression, its multiplicity of subjective forms of “justice,” and its hyper-politicized public sphere where political engagement for some reason lacks efficacy, there still exists a singular and burning desire for authenticity.

According to a certain chronology, the modern era of the mass shooter began with the spectacle of Columbine in the late ’90s. Back then, the perpetrators of mass shootings once came from America’s cultural hinterlands, before moving increasingly into the cultural centers. Now they are increasingly found beyond its physical borders, and the reach of this anomic male violence is as vast as the internet itself; its perpetrators’ capacity for violent retribution unbounded and seemingly objectless. Deranged by a slavish addiction to technology, incapable of distinguishing between virtuality and actuality, the political class has complacently assumed that these young men will continue to commit ever more horrific acts of mass violence, but instead of attempting to address root causes, have instead made them part of a cynical calculation. They were aided in this calculation by the fact that the psycho-sexual motivations behind these atrocities seemed so incoherent, paltry, and completely undeserving of sympathy.

One of the most influential works of political philosophy in the twentieth century is George Sorel’s Reflections on Violence (1908), which inspired revolutionary movements across both the left and right in the volatile post-WWI era. In the course of his career Sorel was associated with liberalism, conservatism, the reactionary ideas of Action Française and Charles Maurras, latterly with Marxism, and eventually with Anarcho-Syndicalism. Sorel believed violence to be the primary creative force of history, the best means to counteract the complacency of bourgeois centrist plutocracies and their favored ‘democratic’ forms of government. The General Strike was for Sorel a highly aestheticized form of symbolic violence, motivated by a sense of divine justice. In contradistinction to the violence of the State:

Proletarian violence, carried on as a pure and simple manifestation of the sentiment of class struggle, appears thus as a very fine and heroic thing; it is at the service of the immemorial interests of civilization; it is not perhaps the most appropriate method of obtaining immediate material advantages, but it may save the world from barbarism.

Significant here is that Sorel considers this potent form of violence symbolic. The distinction was further elaborated by Walther Benjamin as the difference between “mythical” violence and “divine” violence, in which we may find echoes of recent events:

God is opposed to myth in all spheres, so divine violence runs counter to mythic violence. Indeed, divine violence designates in all respects an antithesis to mythic violence. If mythic violence is law-positing, divine violence is law-annihilating. . . . Mythic violence is blood-violence over mere life for the sake of violence itself; divine violence is pure violence over all of life for the sake of the living.

A little more recently, Slavoj Žižek responded to Benjamin’s critique:

Divine violence should thus be conceived as divine in the precise sense of the old Latin motto vox populi, vox dei . . . as the heroic assumption of the solitude of sovereign decision. . . . If it is extra-moral, it is not “immoral.”

Many view Mangione’s action through the prism of this type of revolutionary “divine” violence: Yet its brutal characteristics—far removed from the symbolic violence of the General Strike which for Sorel served Civilization—bear some resemblance to the mythical variety of “blood-violence over mere life for the sake of violence itself.” In this sense, Sorel’s choleric work still has much to say about the present, evidenced by the sophisticated social, political and technological controls still used to counteract revolutionary violence.

Some of those responsible for upholding these controls regard the current era of the mass shooter in the terms of a “Sacrificial Crisis” as described by René Girard in his Violence and the Sacred (1972). Girard maintained that mimetic violence and vengeance—i.e. copycat violence—would proliferate when the rites and rituals once used to keep them in check no longer functioned. In the absence of the surrogate sacrificial victim—or a system of ritual or religious practice which can mimic this function—the “contagion” of reciprocal violence would spread mercilessly through human communities, eventually leading to their implosion and destruction. The sense of distance from this brutal atavistic reality created by technology in advanced “civilized” societies has, according to Girard, lulled us into a false sense of security:

We have managed to extricate ourselves from the sacred somewhat more successfully than other societies have done, to the point of losing all memory of the generative violence; but we are now about to rediscover it. The essential violence returns to us in a spectacular manner— not only in the form of a violent history but also in the form of subversive knowledge. This crisis invites us, for the very first time, to violate the taboo that neither Heraclitus nor Euripides could ever quite manage to violate, and to expose to the light of reason the role played by violence in human society.

In this enigmatic conclusion, Girard’s essentially pessimistic worldview comes to the fore. Significantly it is one which continues to exert significant influence on contemporary thought. In 2007 the entrepreneur and writer Peter Thiel penned an essay in an obscure academic book series dedicated to René Girard, whom he had followed in his Stanford days. Written in succinct and eloquent prose, “The Straussian Moment” gives Thiel’s account of the impasse presented to the West by the terrorist attacks of September 11th as seen through the work of John Locke, Carl Schmitt, Leo Strauss and Girard himself. Thiel contends that the central assumptions of the Enlightenment were forms of retreat. Forged in the long shadow cast by the Thirty Years War and the Peace of Westphalia, the emergence of liberal democracy resulted from a compromise. The enlightenment values which underpin contemporary democratic ideas are based upon an agreement to defer fundamental questions about the truths of human nature, rather than a system of optimum governance modeled on those truths:

From the Enlightenment on, modern political philosophy has been characterized by the abandonment of a set of questions that an earlier age had deemed central: What is a well-lived life? What does it mean to be human? What is the nature of the city and humanity? How does culture and religion fit into all of this? For the modern world, the death of God was followed by the disappearance of the question of human nature.

In his brief discussion Thiel also takes account of Carl Schmitt’s The Concept of the Political (1932) focusing on Schmitt’s discussion of the concomitant processes of hyperpoliticization/depoliticization that precede the later emergence of a “Total State”:

[I]f civil war should forever be foreclosed in a realm which embraces the globe, then the distinction of friend and enemy would also cease. What remains is neither politics nor state, but culture, civilization, economics, morality, law, art, entertainment, etc.

For Thiel, the Total State which Schmitt describes is, from one perspective, something to aspire to, and one eminently achievable through the intervention of technology:

The world of “entertainment” represents the culmination of the shift away from politics. A representation of reality might appear to replace reality: instead of violent wars, there could be violent video games; instead of heroic feats, there could be thrilling amusement park rides; instead of serious thought, there could be “intrigue of all sorts,” as in a soap opera. It is a world where people spend their lives amusing themselves to death.

Thiel recounts how Schmitt regarded the potential emergence of such an artificial world through technological faith as the malevolent work of the Antichrist; a world of tenuous peace and security that will briefly reign before “the final catastrophe.” Although conceding that the “price of abandoning oneself to such an artificial representation is always too high,” what are we to make of Thiel’s involvement in funding and supporting various companies that have helped engender the contemporary supremacy of these same artificial representations? The answer is to be found in the tension that exists between the thought of Leo Strauss and Girard in relation to the role of violence in human societies. Strauss, Thiel maintains, does not necessarily disagree with Girard—but is in no way bound by Girard’s Catholic universalism, and is loyal only to the interests of an initiated elite. It is, Thiel maintains, a question of timeliness:

For Strauss as for Nietzsche, the truth of mimesis and of the founding murder is so shocking that most people, in all times and places, simply will not believe it. The world of the Enlightenment may have been based on certain misconceptions about the nature of humanity, but the full knowledge of these misconceptions can remain the province of a philosophical elite. The successful popularization of such knowledge would be the only thing to fear. . . .

Thiel ends on a note of ambivalence. The modern age may well not be “permanent,” but it has not yet come to an end and there is no telling how long it will endure. In the meantime, it is better to “side with peace” over violence. And even though one day “all will be revealed,” and all injustices will eventually be “exposed” and the perpetrators “held to account”—the decisions made by those who rule will “determine the destiny” of the world to come. In one reading, Thiel’s proposition advocates for the technological Total State and its various forms of entertainment qua mass deception and control as a means to hold back the “limitless violence of a runaway mimesis,” thereby ensuring the rule of a powerful esoteric elite. In another it reads as a noble and benevolent strategy aimed at preventing wanton violence for the maintenance of peace and order for as many people as possible, for as long as possible. In both readings what is clear is that Thiel, in his dual role as religious pessimist and libidinal engineer, is unequivocal in his belief that the sine qua non of any form of elite domination over the masses is the ability to place controls upon violence.

An examination of Luigi Mangione’s Goodreads account is telling for a number of reasons. Yet little attention has been given to the clear disparity between the books he read, and those which he aspired to read. The former, less numerous, category is filled with work of popular sociology and psychology, economics, dietary advice, meme-tier cultural criticism, self-help, and genre fiction. The latter contains some dense philosophical and literary, work which can be regarded as “improving” in the best sense. The difference speaks to the struggle faced by many in distinguishing between virtuality and actuality, between a stultifying and immiserating technological society that only offers the consolation and justification for pain, against the hope for a world in which the suffering of Pain is to be endured if it approaches higher principles.

Mangione’s review of Ted Kaczynski’s manifesto, curiously located in the former category, is telling on many levels:

While these actions tend to be characterized as those of a crazy luddite, however, they are more accurately seen as those of an extreme political revolutionary.

And further, apparently paraphrasing a “take” he found online, he states that Kaczynski:

Had the balls to recognize that peaceful protest has gotten us absolutely nowhere and at the end of the day, he’s probably right. Oil barons haven’t listened to any environmentalists, but they feared him. When all other forms of communication fail, violence is necessary to survive.

To understand the import of these statements, it would be useful to turn to an excellent yet obscure philosophical text written in 1998 by Eric Krakauer, erstwhile philosophy scholar and now a physician and Professor of Medicine at Harvard medical school. In this text, Krakauer provides a valuable diagnosis of the insurmountable problem posed by the dialectic of technology:

Technology has progressively turned the technologically generated autonomous human subject into a heteronomous object for technological domination. This reversion has occurred as the technologies of the culture industry have totalized a certain mode of thinking. The same technological or “dispositive thinking” with which the subject masters nature now enslaves the subject as it totalizes both itself and society.1

The only possible antidote to such a grave prognosis will come by embracing what novelist and firebrand Wyndham Lewis’s called the stalled revolution of the Luddites. The Luddite movement was not a mere paroxysm of lumpen discontent, borne of fear and ignorance, and misdirected towards what Karl Marx dismissed as the “material instruments” of production rather than its modes. The Luddites’ primary grievance was not with the form of machinery itself, nor towards a technology they did not understand (indeed many of them were highly skilled machine operators). Rather, it was with the ways in which the threat of technology was being exploited by a parasitic ownership class to degrade working conditions. Over the course of time, within the popular imagination, as is evident in Mangione’s reference, the term has become derisory. To be a Luddite is to be ignorant and fearful of technological progress whilst nostalgic for an illusory past. For Lewis, however, the technological revolution began not with the invention of machines but with the Luddites’ demand that the machine be subjugated to human needs. He saw within their attacks against modes of production which favored machines, the struggle for human subjectivity over heteronomous technological subjugation.

Lewis’s first-hand experience of the First World War cauterized his opposition to what was previously a fascinated ambivalence toward technological advancement. In common with Lewis, I believe that an insistence upon the fundamental incompatibility of man and machine does not signal a naïve desire to return to a mythical prelapsarian past. It is rather a weary insistence that all fantasies of machinic desire spring from a profoundly damaged consciousness, that any temporary easing of the burden of human existence that comes from elevating machines to sentience, will never replace what will be irrevocably be lost.

I believe we must draw a strong distinction between what I call the “normative” and “recidivist” forms of masculinity, the former eminently worthy of repurposing and revitalization—the latter immeasurably transgressive and destructive. A public discourse which refuses to make such distinctions and relies instead on journalistic platitudes will mean that an honest, and necessary, account of masculinity’s relationship to violence will continue to elude us. Most seemingly cannot break free from a form of analysis that views all expressions of an (undifferentiated) masculinity as retrograde and inculpatory ad initio; something to be acknowledged only grudgingly, if not eventually effaced and dismantled altogether. Social constructivist perspectives such as these are widespread, but they will find difficulty in explicating the rise in chaotic violence as more recidivist subjects are created by the untrammelled anomie of the technological quotidian. An honest account will derive only from a re-consideration of violence itself and its role as a form of symbolic power which can, if properly conceived and sublimated, potentially be made to serve productive ends.

The grim alternative can be envisioned by considering the enigmatic pronouncements of Yukio Mishima, who declared himself in favor of violence whether of the left or the right. Mishima’s statement was no mere provocation but an attempt at mediation. Speaking to a packed auditorium of communist and socialist student radicals—some of whom openly declared that they only came to see him beaten to death—Mishima’s comment alluded to the power of violence as (divine) potentiality, as a point of commonality between the radical students’ struggle for revolution and his own quest to make his life into a work of art. It remains a difficult lesson for us to grasp, but an essential one nonetheless. Arguably one of the most gifted aesthetes in the modern Japanese tradition, from a young age Mishima expressed a morbid fixation with death, which he was ultimately unsuccessful in containing only within his remarkable body of work. In the lead up to his theatrical coup d’etat in 1970, Mishima had himself photographed by Kishin Shinoyama in a series called “Death of a Man.” He posed in various mythically violent scenarios; drowning in mud in one, with a hatchet embedded in his head in another; crushed under the wheels of a truck in the next, then as Saint Sebastian dying in ecstatic agony from his arrow wounds which evoked the famous renaissance painting by Guido Reni, and finally as a Samurai committing Seppuku. In the end Mishima chose the mimesis of profane violence. This is the path of recidivist masculinity. Self-reflexive, self-aggrandizing and self-mythologizing—we must always remember that he could only attain his so-called “beautiful” death under the camera eye of technological subjugation, a maddeningly cruel gaze which today has become an all-encompassing panopticon. Against the power of this monstrous inhuman monolith, death may seem like a welcome reprieve. But it is always much harder for a man to keep living, to preserve life, than it is to destroy it. It remains possible to harness the symbolic power of “divine” violence, to reject the call for mythic violence which exists only for its own sake. The solution might be found in Sorel’s view of the General Strike, an act of collective symbolic violence which ultimately serves the interests of civilization, and prevents the descent into barbarism.

Eric L. Krakauer, The Disposition of the Subject: Reading Adorno’s Dialectic of Technology (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1998), p. 116.

Nice essay but I have a hard time believing that x-ray is legit.