In June I’ll be publishing my first novel, Stop All the Clocks, through Arcade Publishing. (Follow their Substack! Click the nice banner image below!) When they signed on to publish the novel, they also signed on to publish a non-fiction book, The Mystagogues. I haven’t spoken or written much about The Mystagogues. I don’t even have the elevator pitch for it down yet. But it’s the thing that is currently occupying most of my time, and for which I feel most passionate. By a country mile. So I wanted to share some of the ideas behind it with you.

Probably I should have done this before now, but I’m a little old-fashioned. Writing pages and pages of stuff and putting it in the drawer and never showing anyone is easy for me. Sharing work on social media is like pulling teeth. (Except I have to pull at least one tooth a day on each increasingly sloppified platform, and schedule the extractions on Airtable.) It feels especially hard to bang the drum for something that I’m still in the process of composing and which hasn’t even revealed to me its full form.

At the same time, it’s clear the direction the world of writing and reading is going—with consistent blogging becoming more and more important—and I suspect it will behoove me to post consistently about what I’m up to with The Mystagogues. I also suspect that a lot of people will be interested. The concerns of the book are deeply important to me; sometimes I feel that they’re far more important than anything else in the world. Not only that, it seems to me that I have a relatively rare window onto a field that is unfairly neglected, and ideas that may lead to some important advances.

The piece below isn’t necessarily the best entry point to The Mystagogues, but it contains some central ideas and works as a self-contained whole.

To orient you a little better, here are three project-summarizing paragraphs from the book proposal of The Mystagogues:

Ours is a strangely desiccated era for the study of religious thought. Modern scholarship has shown without a doubt that the world’s great religions have more in common with one another than the pre-moderns could have ever imagined. The myth of the flood can be found in sacred texts spanning the globe. The myth of Christ can be dated to a time long before the historical Christ—the Ancient Sumerian version of the myth even tells, as does the Bible, of a common criminal being tried alongside the soon-to-be-slain god. And iconography from our Abrahamic religions clearly has a basis in ancient astrology as practiced in ancient India and Egypt. For instance, the tetramorph seen often in Catholic cathedrals refers to the four fixed astrological signs representing the cardinal directions (Aquarius = man = North; Leo = lion = south; Taurus = bull = west; Eagle = Scorpio = East).

One might think that these circumstances would lead to a flourishing field of scholars working to determine the true nature of religion. And yet the reality is quite the opposite. (It is perhaps the case that “investigating the true nature of religion” is one of those tasks that is so large and obviously necessary that it goes unseen and untried.) Gone are the great syncretists such as Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and Mircea Eliade. Instead, we have on the one hand psychophysical reductionists who assume a priori that religion is merely a mystification and facade. On the other hand, today’s scholars who do practice religion increasingly find it appropriate to retreat back into parochialism: besieged by a world of hedonistic nihilism, they no longer bother worrying about why one religious faith and not another might be correct. Who today, for instance, would deign to listen to a debate over the soundness of Anglicanism vs. Catholicism?—yet this was a controversy that shook British academia to its roots during the conversion of the great writer and saint John Henry Newman. And so the religious retreat back into their separate, unsystematic corners. Meanwhile, in our public life—among politicians, church leaders, and pundits—what is called religion is typically no more than a cudgel for beating the populace into submission to various opinions on ethical behavior. But any serious student of the phenomenon of religion will quickly find that at the heart of it is far more than merely political control. An understanding of Christianity, for instance, should account for the poetic inspiration of Dante, for the asceticism of the desert fathers, for the mystical visions of Hildegard von Bingen and St. John of the Cross, for the mysteries of the Book of Revelation, and the strange iconography of Botticelli and Bosch.

What then would a healthy study of comparative religion look like? To begin, it should take seriously the perennialist position—which is, at least implicitly, the position of the five writers whose lives and work will be discussed in this book: Robert Graves, Colin Wilson, Vladimir Nabokov, Roberto Calasso, and Ioan Culianu. The perennialist position can be briefly summarized, although a sound argument in its favor would require multiple volumes. Perennialism is the belief that an ancient wisdom far older than the Abrahamic religions is at the core of a mysterious mode of thought that was eventually transmitted to us throughout the world’s most cherished ancient texts—from Greece to ancient Sumer to ancient India.

Without further ado:

God through the Ages

We tend to think of God as Something static. Given His immortality and omnipotence, one feels He ought to at least to be regular in His habits. No one likes the thought of a mercurial God, although Mercury himself was a god, and although, when you get down to brass tacks, the God of the Old Testament can be about as dependable as a petulant teen. In the Book of Job, for instance, God is obviously evil. God’s torture of Job does not have a moral, try as we might to find it; it seems to have more in common with Michael Hanneke’s sadistic romp Funny Games than with any tale of Aesop. This is why—a rarity among Bible stories—Job serves as such excellent fodder for art—having inspired Robert Frost’s A Masque of Reason, Archibald MacLeish’s JB, and the Coen Brothers’ A Serious Man.

One prominent noticer of this ugly fact about God’s occasional propensity to evil was Carl Jung. Jung believed that answers to theological questions should come in fours, not threes. Thus the Trinity is missing a Very Significant Person: the Devil, who makes of it a Quaternity. This explains the otherwise thorny question of why evil exists. As Jung writes in Answer to Job:

The idea of the privatio boni began to play a role in the Church only after Mani [the originator of Manichaeism]. Before this heresy, Clement of Rome taught that God rules the world with a right and a left hand, the right being Christ, the left Satan. Clement’s view is clearly monotheistic, as it unites the opposites in one God.

Such ideas prick Western religious ears (if there are still such ears to be pricked) but harmonize better with eastern religious notions grounded in the idea that there can be no light without darkness and no good without evil. This at least does not offend logic, and does not require the reflexive intonation that questions of needless suffering are beyond human understanding and must be accepted on faith.

More shocking, perhaps, in Jung’s Answer to Job, is the idea that God, like man, develops. For Jung, with the birth of Christ, God becomes more humane in a double sense: He sends his Son to earth to die not to expiate the sins of mankind, but to expiate His own.

Jung wrote Answer to Job in 1954 in a literal fever. The circumstances suggest that Jung only put these blasphemous ideas down on paper out of a fear that he might soon die. That God should evolve would have been a very strange idea indeed to Jung’s readers in 1954, and it feels unlikely that anyone who valued his intellectual respectability would have offered it. And yet the idea had already been brought forth in 1930, by a British poet and ex-soldier who had just burned his bridges in England with a brutally honest memoir of schoolboy sadism and wartime cowardice, and now found himself starting a new life with his Jewish American mentor-mistress on the rustic island of Mallorca.

As usual, Robert Graves had been in dire need of money, and had recently been spending eighteen hours a day writing his memoir Good-Bye to All That, which he felt would cause a scandal and which did so—climbing the bestseller charts and mortifying his pious, octogenarian father to such a degree that Graves pére clapped back with his own memoir, To Return to All That. After the publication of Good-Bye to All That, Robert Graves found himself without a grand project to take on, yet unable to get out of the habit of working every waking hour. And so he began writing diary entries which he called “A Journal of Curiosities,” which can are collected in the rare 1930 publication But It Still Goes On. This journal took on such subjects as “the problem of publicity” and “the feminine word-ending -ess.” The last curiosity is the most curious of all. “Abandoning myself to the triviality of this journal,” Graves writes, “is rather like putting myself in God’s hands and leaving it all to Him.” With that sentence, like an abracadabra, the idea takes hold. The next entry begins with quotation marks. The imagined speaker is God himself.

God begins by informing the reader that he first came into the world under the name of “Juju.” Graves translates Ju as Why and claims it is cognate with the French dieu and thus with deus. The duplication of Ju comes from a familiar refrain among those seeking answers: Why? they wonder, when the crops go dry. And Why!, they exclaim when the rain comes to replenish the soil. God is both the question and the answer. And the answer is a tautological one, just as our answer to the question of why we exist is a tautological one: We exist, we say, because a single point int he universe expanded and because prokaryotes became eukaryotes and because consciousness inexplicably emerged among monkeys. Why? Why!

Graves also asserts that tabu or taboo comes from Taba-ju, meaning not juju. Thus a tribe that identifies with the deer is prohibited from eating deer meat, and a tribe that identifies with the goat is prohibited from eating goat meat. More crucially, young girls from the goat tribe are made honorary deer, and young girls from the deer tribe are made honorary goats—thus encouraging inter-tribe cooperation, and discouraging incest and the breeding of girls at too young an age, since, having been born into the “wrong” tribe, they must ambulate across the valley in order to mate. This leads to a situation in which biological fathers are not recognized at all; rather, the mother’s brother is the man who takes an interest in the child. This is the sort of large-family matriarchal society that has lately come to be described as the longhouse.

Anticipations of the White Goddess

It has been suggested by Graves’s lover and collaborator Laura Riding and by subsequent scholars that Graves’s central ideas in his most famous scholarly work, The White Goddess, were cribbed from Riding. Certainly she had an intense influence on Graves, but it is worth noting that all the ideas that went into that book existed germinally in writing that Graves published before he and Riding met. Graves’s interest in pre-Abrahamic matriarchal societies finds its way into his first novel, the rare and rarely mentioned 1925 My Head! My Head!, and probably came down to him from the pioneering psychiatrist and anthropologist W. H. R. Rivers, who treated both Graves and Graves’s close friend, the war poet Siegfried Sassoson, for shell shock. Rivers was a predecessor of the better-known Bronislaw Malinowski, whose field work would become famous. Malinowski’s studies of Papua New Guinean tribes which knew nothing of biological fatherhood were famous to enough to to have been cited by Bertrand Russell in his 1929 “Marriage and Morals,” a tract which dared to question monogamy and which got Russell blacklisted from several jobs at American universities.

Eventually, in Graves’s theologico-anthropological telling, the notion develops that failure to go across the valley for sexual activity is associated with lack of children. Thus the principles of logic and of fatherhood emerge simultaneously. At this point God takes the form of Father. His being assigned a sex, however, is merely incidental; or, perhaps more accurately, it is circumstantial. “I regret this male and female tediousness,” God explains, “though it was, as I say, a necessary part of my evolution.”

Graves’s diary then gives way to a self-contained piece called the “Autobiography of Baal.” Why Baal? The narrator explains that it would be impolite for him to use the more common name God; by using Baal, He can go semi-incognito, like a Duke or Baron who travels to foreign lands under the name of some less famous ancestor, fooling no one but avoiding the ceremonial hullabaloo. The autobiography starts as an apologia for God’s most recent works, The Book of Mormon and Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy’s Science and Health. God explains that with these two books he was demonstrating his sense of humor—often an underrated quality of the Deity. This constitutes the first chapter, called “Alpha.”

The second and final chapter is the “Omega” chapter. The narrator jokes that because He is the Alpha and Omega, he is content to submit only these first and last chapters to posterity, and to let the rest be lost. The “Omega” chapter is mightily perplexing and seems—for anyone familiar with Graves’s biography—to hint at the sacred powers of Laura Riding, who not only believed herself divine but (and this is a far rarer and far more interesting phenomenon) persuaded several other of her close associates of this fact. God intimates in this chapter that the next stage of his evolution will involve the .01% of the world over which He does not have dominion. What is the force that falls within this sliver? It’s left to the reader to determine. Ubermensch? The devil? Riding herself?

What is all this about? Just an elaborate joke? Not at all. We have every reason to believe that Graves took his ideas about the evolutionary nature of God entirely seriously. And although he abandoned the Christian faith in which he had been raised, he maintained a sense of religious duty and placed rigorous ethical demands on himself—although in the 1930s his family and and friends did not believe in the ethics of those ethical demands. But Graves was working according to a system. Always in search of mentors, he had found one in the 1920s in Oxford in the form of the Indian philosopher Basanta Kumar Mallik, who came to deeply influence Graves’s understanding of religion and much else.

A short summary of Mallik’s philosophy might help clear things up. From Graves scholar Michel Pharand’s useful essay “A Flash of Lightning and a Crown of Jewels: Robert Graves and Basanta Mallik”:1

Mallik's philosophy is actually very simple, and if we follow his relativist ideology, we can achieve an equilibrium of values, at least theoretically. His "Law of Contradiction"—formulated on Armistice Day 1918, according to Sondhi and Walker (118)—forms the basis of his Conflict Theory and may be summarized as follows: Conflicts oppose pairs of values—freedom and order, individuality and community, monotheism and polytheism, etc.—in which the affirmation of one value leads to what Mallik calls "mythology": persuasion, conversion, suppression and dominance of the other value. "Thus the predisposing mental attitudes to war and other forms of conflict result from the illusion of thinking one's cherished values to be absolute and universal, and of those opposed to them as contradictories which must be completely negated or eliminated. Such thought processes naturally lead to divers expressions of mythology: missions of religious or political (ideological) conversion, military conflicts, patterns of structural dominance, economic expansionism or political revolution." Once "mythology" is seen as ineffective, the parties can try to locate the source of the illusions that engender tension and eventually abstain from conflict entirely. "These efforts will transform individuals who have lived in illusion and perpetual conflict to people with confidence and certainty." But since all opposing values are "mutually dependent" and none is totally "wrong," none are dispensable. "All therefore are deserving of respect tempered with reservation." And since no individual is expendable, "all cultural and social groups needs must be accorded a similar and equal respect."

Readers of Graves’s magnum opus The White Goddess will already recognize in the above passage strains of what would become Graves’s central thesis. That is, all or nearly all religious records of the western world betray a cunning redaction of the Goddess who was worshipped universally before the advent of the patriarchal religions, which are still current today in the forms of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. This thesis at first blush sounds a tad conspiratorial. And yet a brief overview of historiography shows us just how easily our founding myths can be inverted. Whereas in the contemporary record, we find that World War II was an American battle to subdue to the barbarous race of Germans, only 50 years later we find that it was a noble project undertaken in large part to liberate the Jews. It took about half a century to completely alter the meaning of this, one of the biggest events in world history, even in an era when we all have the resources to ascertain truth. Imagine what could be done over the course of millennia, when only few had the knowledge and technology available to craft the story of the world and its inhabitants.

So, whereas in The White Goddess, Graves focuses in on the cult of the Goddess at a particular era in time, in the theological writings collected in But It Still Goes On he makes a more general point and perhaps a more profound point. Graves follows Mallik’s lead in assuming that no value is universal. Any value that is cherished also has an opposite which is also cherished. For Graves, God does not escape this principle. Rather, God is the ultimate form of this principle: the Great Contradictoriness of the universe eternally ironing itself out.

Is God Like the Moon? Or Like Love?

Can we make this a little more concrete? One problem with the word God is that it is overdetermined. It could mean the Creator, the Divine Judge, or Spirituality itself. A modern Jew, Christian, or Muslim likely sees all three meanings as permeating the word God. Can we find a single definition that encompasses all these—from a non-sectarian point of view?

Let’s start with a hypothesis which might lead us toward a more general definition: Very roughly speaking, there exists a science, related to what Wilhelm Reich has called “orgone energy,” the laws of which are described in an esoteric layer of religious texts.

This sacred science hasn’t been kept entirely hidden. Reich is one obvious example of an entirely materially minded person who butts his head up against something that cannot be explained by the current scientific paradigm. But there are many others, and many things under the sun that cannot be dreamt of within the paradigm of our current philosophy.2

Many compendia of inexplicable occurrences exist; but these melt away under the psychophysical reductionist’s general principle that such evidence or such claims are either fraudulent or else will be explained away by psychophysical reductionism at some point in the future. The third option—that the paradigm itself is incomplete—is strictly prohibited. Even certain obvious and well-known physical phenomena poke holes in the paradigm. For instance there is scarcely room for the enormous, inexplicable power of the Placebo Effect under the psychophysical reductionist regime.

We must remember that for ancient peoples religious texts functioned as the entire corpus of civilizational knowledge. There were no self-help books. There were no romance novels. There were no instruction manuals. And thus information about very diverse subjects was grafted onto the same text. Thus the text could mean different things to different readers depending on the level at which those different groups were able to read. For some, the Bible provided straightforward injunctions on the subject of how to manage crops or behave toward women. For others it spoke of deep mysteries into the universe which only few could understand.

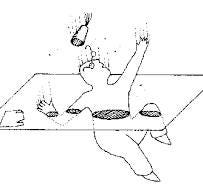

Can modern science help us with any of this? In some respects, the concept of four-dimensionality seems to map quite well onto this abstract definition of God. Take this example. In 1884 an Anglican priest named Edwin Abbott Abbott published a speculative fiction novel called Flatland. The Flatland of the title is a world in which all beings are two-dimensional. There are triangles (peasants), octagons (warriors), and circles (high priests). But they all possess no more than two dimensions and move along a two-dimensional plane. The novel then invites us to imagine what would happen if a three-dimensional object were to accidentally make its way into Flatland. Picture, for instance, a human being. (Actually, you don’t have to picture it, because I’ve supplied below an illustration used in mathematician Rudy Rucker’s excellent The Fourth Dimension.)

At the moment being pictured here, the gentleman falling through Flatland appears to the Flatlanders as four separate circles: one at the right wrist, one at the right bicep, one at the waist, and one at the left knee. When he first appeared, assuming he fell feet first, he would have appeared as only two circles: his legs. As he is exiting, he will appear as only one circle: his head. For the Flatlander, there would be no continuity between the appearance and disappearance of these different circles. They would just be there and then be gone.

Does this not sound rather like our own experiences on earth with various spiritual or religious or occult phenomena? It is one of the main properties of both angels and ghosts that they appear and disappear in a flash, and that experiences with them seem to defy attempts to explain them using regular chronology. UFO sightings, too, follow this pattern: They are phenomena which seem to behave, within three-dimensional space, in ways apparently unaccountable by the laws that govern that space. Meanwhile, in the field of ancient iconography, mandalas and kabbalistic diagrams look suspiciously like unfolded tesseracts (4-dimensional cubes), and geometrical drawings from the likes of occultist and Neoplatonist philosopher Giordano Bruno unquestionably demonstrate a perception of multi-dimensionality.

But this advances us no further toward an answer to one important central question when considering the concept of God. Namely, is God an objective fact or a subjective one? To put it more nicely, is God like the Moon or is God like love?

No one denies the existence of the moon. Even before we had telescopes to examine it, no one denied it. And yet we perceived it only partially, and badly. At a New Moon, we perceived it as a sliver; at a half-moon as a semi-circle; at the full moon as a rotundity. Some observers in some geographical locations would perceive the moon as larger; others would perceive it as smaller. Some would perceive it in some moments as of a reddish hue; mostly others would perceive it as whitish. All through this, it remained objectively the same. There was and is a true map of the moon to be made, given the right tools. One could even visit it, given especially good tools. Is God like this?

No one denies the existence of love. More particularly, no one denies the existence of the state of being in love. And yet there is no objective version of this state of being that can be pointed to and be observed by all. It exists only subjectively, and contingently. The state of being in love requires both a lover and a love object. Moreover, the effects of the state of being in love are highly variable, as are the characteristics of the love object. One can be raised to the greatest ecstasies known to man by being in love; one can also be driven to suicide. One can love a saint, or one can love a terrible sinner. Judging by the fan mail serial rapists and killers like Ted Bundy get when they are apprehended, it may be easier to love a sinner. But the important thing is that being in love can take on just about any permutation. It has no objective shape. It can be used for both good and evil. And yet, somehow, it has a common quality agreed on by all, which we would rather not do without. Is God like this?

This is one of the central questions of the great Romanian philosopher Ioan Culianu. I will discuss this in a later post, and I’ll also discuss something a little more titillating: his mysterious murder in 1991 in a bathroom stall of a classroom building at the University of Chicago. Until then . . . .

The quotations in this passage reference the following text:

Sondhi, Madhuri and Walker, Mary M., ‘Basanta Kumar Mallik and Robert Graves: Personal Encounters and Processes in Socio-Cultural Thought’, Gravesiana: The Journal of the Robert Graves Society 1.11 (December 1996)

a paradigm which I, following the example of philosopher of mind Thomas Nagel, call psychophysical reductionism

Recently read William Irwin Thompson’s “The Time Falling Bodies Take to Light” which traces the evolution of religion and civilization away from the primitive Cult of the Goddess - feels like a similar concept to Graves’ White Goddess - totally rocked my world

Interesting, looking forward to the book. Gimbutas’ work is also in line with Graves’, worth looking into it. I read the Ted Anton book when it came out, which led me to Culianu’s short fiction. Interesting to say the least, like a cross between Eliade (Mircea not Mercia, btw) and Umberto Eco. Not fully realized tho, imo. Sad that he was taken so early. Someone should track down his gf at the time, Hillary Wiesner, I bet she’s got stories…